(This expedition won the IMF Award for "Outstanding Exploratory Civilian Expedition" in 2014)

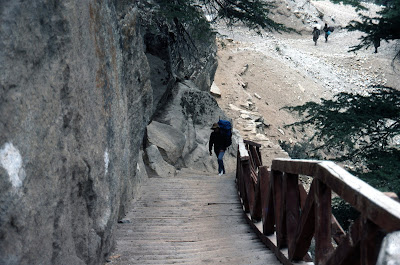

The Shepherd Trail in the Smugglers' Valley

Stage 0- The Drive In

Delhi-Uttarkashi (425 Km)- Dumku (108 Km)

We reached Uttarkashi on 7th June by the

appointed time, 12 Noon. The afternoon was spent shopping for local woolens at our

favorite shop near the Uttarkashi bus-stand.

A Jadh family of Dunda owns this shop. Negi

struck up a conversation with the old Jadh

Bhotia, enquiring about the current Jadh

settlements. After coming to know about our past adventures in Nelang and this year’s expedition

objectives he was visibly excited.

“यह prayer flag ले जाइए साब. अगर आपको वो pass मिल गया तो ऐसे जगह पे लगा दीजिये जहाँ इसे हवा लगे ” said the old man brandishing a

sizeable package from under his desk.

“कितने पैसे हुए इसके?” I asked.

“अरे पैसे क्या साब. यह तो हमारा gift है - Jadhon का prayer flag. आप हमारे यहाँ पुराना route ढूंढने जा रहे हो . यह तो अच्छा काम है.”

We later gathered that the handcrafted prayer flag would

have fetched him about a thousand Rupees in a normal transaction, which he so readily

offered us free of cost. His trust on us, that the gift would be well used,

added one more reason for successful completion of the expedition!

The invite from Commandant

Chandel was a pleasant surprise later that day when we went to pay the

customary visit to the ITBP Headquarters

at Matli.

“Get your entire party in the evening. Lets have a drink

together. We shall meet at the lawns of

the Officer’s mess!” said the commandant putting us instantly at ease,

nipping out any apprehension that we might have had about

dealing with the ITBP personnel.

The evening was spent in a nice chat with the senior

officials of the ITBP Battalion that

looks after the Nelang area. We fondly recounted our experiences with

ITBP during our expedition to Girthi Valley a few years before when Commdnt Chandel was the CO at Joshimath.

“I really like that people like you continue to take

interest in such (inaccessible) parts of the mountain..”- The commandant was

all praises for trained civilians experiencing the extreme mountains.

As the discussion veered round to the route into Nelang and the interesting plank bridge

near Gartang, he was quick to advise

“Do not even try walking over that bridge now. It is without

maintenance for many years and the wood planks are badly rotten”- The Dy Commandant then filled us up on their

recent experience of reconnaissance in that area.

“Go meet the Asst

Commandant at Nelang around 1400

Hrs and he should be able to help you with a briefing about the route. You will

have to meet him anyway for showing your papers. That’s the nearest post before

you leave road head”- said the CO.

Few drinks and many plates of snacks later we were a happy

and peppy bunch coming out of the gates of the Matli complex at about 2200Hrs in the night. Tomorrow would be our

first camp on the banks of Chor Gad.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

“आप इतने देर कहाँ थे? CO साब ने दो बार phone कर के पूछा. आप को दो बजे आना था कह रह थे.”

The post commander at Nelang

was waiting for us at his snow-dome office when we arrived there to show the

papers at 1530.

“थोड़ा देर हो गया Sir रास्ते में. Pagal Nala बढ़ा हुआ था”

We mentioned about the half an hour delay in crossing an engorged nala about 10

Kms before Nelang.

“कोई बात नहीं. चाय लीजिये जब तक मैं आप को route बताता हूँ..” and he started off reeling out route details for the next half an hour.

We absorbed as much detail as we could cross verifying with the terrain map

printouts we were carrying.

After the download of local route intelligence we were much

more confident of the navigation and it looked as if our pre-designed route

plan and time schedule was almost 90% on target. The only thing that could

damage our chances now was the weather and possible terrain challenges during

the decent to the other side of Chunsa

Khaga.

We had dropped the team off at Dumku on our way up to Nelang

so that porter-loads could be made while we were completing the

formalities. By the time we reached back at about 1630, the team was ready for

the short march down to the Metal-bridge over the confluence of Chor Gad and Jadh Ganga.

The Jeeps in which

we had come left back for Uttarkashi immediately

fearing further problems at the Pagal

Nala. We went ahead to pitch the Bridge

camp about a Kilometer away from the road head of Dumku.

The vertical rock faces of granite around the Dumku-bridge camp make for some interesting observations.

|

| (The Bridge Camp at Chor Gad confluence) |

The team seemed to be in fine fettle even as the constant

roar of the two rivers at the confluence reminded us continuously of the raw

power of nature surrounding us. Driftwood was plentiful nearby. Soon we had our

first campfire.

As per our discussions at ITBP-Nelang we had to target at least 12 Kilometers of march the

next day to reach Helipad#3 camping ground (mentioned in the maps as Singhmoche Camping Ground). We started

off lazily around 0800 Hrs even as the sun shined gloriously upon the eastern

bounding ridge of the “Chor Gad” valley:

The Smugglers valley.

>>>>>>>>>>

A Note about the “Chor Gad”

>>>>>>>>>>>

How and when the valley got to bear this notorious name is

still unknown.

Since the days of the early visit of Herbert in 1818, the westernmost valley of the Nelang watershed has always been indicated under this curious

sounding name; Chor Gad. “Chor” in Hindi means a thief and hence the

possible local legends about tax evaders using this valley. Who were the smugglers, what did they smuggle

and which tax did they evade etc. have never ever been documented.

In the melee of Tibetan

sounding names in the same watershed (Nelang/Jadhang/Sumla/

Thag La/Puling Sumdo/Chunganmu/ Tsang Chok La) how the “Chor Gad” carried its distinctive Hindustani flavor is also unknown.

One hypothesis could be- after the Bushaher-Tibet treaty[i] of

1680, the able administration of Kehri

Singh would have exploited trade through Nelang Pass. For securing this interest, they would have had to

assert control over Nelang Pass through the Chor Gad valley.

Perhaps in those times, Bushaher may have played a role in christening of the valley with an overtly Hindustani name unlike others in that watershed.

Perhaps in those times, Bushaher may have played a role in christening of the valley with an overtly Hindustani name unlike others in that watershed.

The alternate hypothesis could be built from the

extraordinarily detailed research of the famous Schlagintweit Brothers. Their work was based on the explorations they

carried out in the 1855-1858 period. They clearly mention the name of the

western-most tributary of the Nelang

watershed as, a very Tibetan looking,

Tsor- Gad [ii]-

not Chor-Gad.

It may not be too far fetched to imagine that the former may

have been the original Tibetan name that over a period of time could have

gradually devolved into the later. The Schlagintweits have referred to the

river as Tsor Gad with out any

journal reference, which would mean that the data was collected from direct

oral accounts during their prolonged exploration of the area.

>>>>>

Stage I- Shepherds’ Trail to Bushaheri Nala

Dumku 3300 M- Misosa 3700M (12 Km)- Thandapani 4050M (12 Km)-

Kalapani 4350M (6 Km)

The route snaked its way along the true left of the river

for the initial kilometer or so and then across a metal bridge to the true

right. Another hour of spirited walk took us past the Lal Devta #1 camping ground

and then onto another possible campsite that on our Map was indicated by the

old name of Namti. The ITBP calls

this camping ground Helipad #1. Though

these are good grounds, accessibility of water is an issue.

“ Dumku से तक़रीबन डेढ़ kilometer baad लाल देवता #1 ayega. अच्छा camp ground है लेकिन पानी का दिक्कत है. उसके थोड़े आगे बकरीवालों का डेरा है पानी के पास, वहां अच्छा पानी मिलेगा.” I remembered the detailed

briefing by Asst Commandant Dimri of

the Nelang post.

“ उसके थोड़े आगे हमारा winter camp-ground है - Helipad #1. वहां पानी मिलेगा main नदी से.”- His information had been detailed and

accurate.

“कोई बात नहीं – आप लोग आराम से Heli #3 तक पहुँच जाओगे पहले दिन. नाले में गन्दा पानी आता है वहां. हमने चस्का बना रखा है साफ़ पानी के लिए एक पत्थर के पास..” the post commander had added.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

A Note on Lal Devta(s) of the Chor Gad valley

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

|

| (Lal Devta #1, Chor Gad Valley) |

The practice of Lal

Devta worship is seen frequently, in the valleys that Jadh Bhotias stay in. Both Jadung

and Harsil valleys are fine

examples of these. The typical Lal Devta shrine

is located at a high place involving reasonable toil to reach. Such shrines are

never more than one in number in a single valley and are usually identified by

piles of Bharal Horns, empty bottles,

dry coconuts and similar offerings.

None of the Lal Devta shrines

in the Chor Gad valley display these

features. There are no offerings, neither are there the customary Bharal horn, bells and the colorful

prayer flags; the “devta” status is

only justified by the red pennant tied to a flag pole. But then that is

precisely how Survey poles were

indicated in those days – a red pennant on top so that it could be recognized

several miles away through the theodolite to triangulate positions!

It may not be too much to assume that it was perhaps the

surveyors like Herbert, Kinney, Ottley and Auden who might have played an influential role in introducing the concept

of Lal Devta into the Chor Gad valley by way of erecting

impressive survey cairns in various high points.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Soon enough we reached a camping ground, indicated on the

map as the Langling Camping Ground,

with signs of step cultivation nearby.

The increasing roar of the river indicated the approaching confluence where

the Chaling Gad from the true right

joins in with the Chor Gad.

The confluence is not visible from the trail but one does enter a boulder field indicating the widening of the river bed just before the confluence. After the boulder field we recovered a faintly visible trail, running along the true right of the Chaling Gad.

|

| (The boulder field at Chaling Confluence) |

The confluence is not visible from the trail but one does enter a boulder field indicating the widening of the river bed just before the confluence. After the boulder field we recovered a faintly visible trail, running along the true right of the Chaling Gad.

We were eager to locate the log bridge over this stream. During the half a kilometer of anxious

searching, as the path wound up along the right bank of Chaling Gad through dense forests, we presently came across a group

of four shepherds with as many mules heading down towards Dumku.

After a brief download from them on the route features ahead, we soon saw the sturdy log bridge laid across the Chaling Gad.

|

| (The forest trail where we met the muleteers) |

After a brief download from them on the route features ahead, we soon saw the sturdy log bridge laid across the Chaling Gad.

The bridge is about half a kilometer above its confluence

with the Chor Gad. We found all the

bridges in the valley in fine condition, seemingly undamaged by the unusual

precipitation and disastrous flooding that gripped the whole of Garhwal in the monsoons of 2013

After gaining the opposite bank, a short scramble of about

100 meters brought us onto a table top upon a small densely wooded hillock.

This hillock rules over the Chor Gad -Chaling Gad confluence and perhaps can

be called as the Chaling Hill or Chaling Jungle. The ITBP and Shepherds

however, conveniently called this the Lal Devta hill. No real sign of Lal Devta worship exists here though,

other than the remaining vestiges of, perhaps an old survey cairn and its

ramrod straight 15 ft long flagpole.

The dense pines grove around the Lal Devta rock provided us the much-needed shade for resting as we

waited for the team to regroup. This was the first day and the physical

challenge was apparent on the face of few team members. It took us two hours to

regroup and then we made a huge navigational blunder!

I had sent out Joshi, the senior-most porter and seasoned

fuel carrier of the team to reconnoiter the route ahead of Lal Devta. I had assumed the route to be moving easterly, directly

descending to the Chor Gad below.

“Lal Devta #2 से सीधा उतराई है bridge तक . Bridge के पास भी आप camp लगा सकते हैं ”- The

Nelang post commander had said

earlier.

“ढलान बहुत है साब . रास्ता उधर से होगा”- said Joshi, as I looked towards the northerly

direction being pointed out. A trail was

snaking into the jungle on a level ground.

We committed the blunder about 200 Meters down this trail

where it bifurcates into two– one moving left upstream and the other downstream

towards the right. We chose the former and lost considerable time and distance

trying to locate the bridge across the Chorgad.

After an hour of anxious search and a kilometer of

unnecessary trudge we finally found ourselves on the left bank of Chor Gad. Conveniently around the same

time we found the muleteers we had met in the morning returning back. They

slowly inched ahead of us and were soon away from our visible range within an

hour.

Their trail led our way now on.

Half an hour after gaining the left bank we entered the

gentle yet frustrating slope of the Misosa

grounds. Within another hour we had crossed over the Misosa stream coming from the glacier fields high above to our

right.

I saw the shepherds’ mule train vanishing over a rising

slope about a kilometer ahead even as we approached the sprawling Misosa camping ground with signs of few

old shepherd encampments nearby. The Misosa

CG is located almost on level ground with the Chor Gad flowing fast less

than a hundred feet away.

The team had again grown a long tail and radio enquiries

revealed that the farthest members were at least an hour behind. It was already

1430 hrs and the sun was on its way down towards the western ridges. I decided

to camp rather than pushing for the additional 2 kilometers to the Singhmoche Camping Ground (Helipad #3 as the

ITBP men called it).

Camp was set up on the right bank of Misosa stream well above the traditional camping ground. The

quality of water on the Misosa stream

was much better compared to the muddy waters of Chorgad that at the campsite below.

Our fully laden porters had already covered 12 Kms on the

first day and the net altitude gain was 600 Mtrs; an impressive feat by all

standards. As for the six of us, our unpracticed limbs were acclimatizing to

the mountain environs rapidly.

Shortly after setting up camp we had an unexpected visitor from

the neighboring campground on the left bank of the Misosa stream. He was a shepherd who had started off from Dumku that morning an hour after we

started and had covered all the ground with his flock of about three hundred

heads of goats and sheep. The poor animals were now afraid to cross the log

bridge over the Misosa stream and the

poor chap was now resigned to bivouac there for the night..

Dead wood and half burnt logs were plenty in the vicinity.

While the kitchen got active in preparing pakodas

and tea, we setup a nice campfire and invited the shepherd over for a

tete-e-tete. We had enough route intelligence already; we wished to now dig

into the life and history of the men who were regular visitors into the valley.

The thirty something shepherd Tilak Raj, with weather-beaten skin and twinkle in his eyes, was

enthusiastic in his narration. At the

end of an hour of chatting up we had gathered the following interesting trivia.

All the shepherds operating in the Chor Gad valley were from one geographical area in the Kangda valley of Himachal. They were two different groups of shepherds

who had well demarcated grazing rights in the upper and lower part of the

valley’s rich pastures. Tilak belonged

to the one with rights of the Upper

Chorgad valleys. Because of the heavy snowfall in the winter, they were

making a late entry hoping that by the time they reach their targeted grounds,

snow conditions would more favorable.

Another seasoned shepherd called Govind Singh whose muleteers we had met in the morning led the

other group of shepherds. They had moved into the valley already and may be

camping a little distance ahead at the Changdum

plains (called Helipad #2 by the men from

ITBP).

“दो number helipad के पास आप को shepherd मिलेगा गोविन्द. नाक उसका थोड़ा सा टेढ़ा है … भालू ने attack किया था उसको कभी” – the officer at Nelang had briefed us earlier.

When our discussion veered towards the objective our

expedition, Tilak fondly recalled the

Tapan Pandit’s visit in 2009. He narrated

how he had met Tapan Da’s team near Thandapani camp. That’s when he mentioned

that the Nala ahead of Thandapani and Dudhpani was called the Kalapani

camp, which was also called the Bushaheri

Nala by the shepherds.

“बुशहरी नाला क्यों कहते हैं उसे? क्या बुशहर का रास्ता था वहां से?”

“हो सकता है शायद. यह तो बहुत पुरानी बात है, हमारे पुरखों के time का”

“कब से आते हो यहाँ ?”

“ बहुत पीढ़ीओं साब। परदादा के परदादा के टाइम से भी पहले …”

We were a satisfied bunch that evening. Not only because the

story telling around the campfire was romantic but also because our research

seemed to have been in complete alignment with the shepherd legends of the

valley and our navigation plan seemed to be bang on target.

We just needed to

execute our plans swiftly and carefully.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

The picturesque trail next day first led us along the

riverside over a kilometer long marine drive. Then it rose sharply for about

200 meters as we emerged upon a boulder field. The field was separated from the

high bank of the river by a grassy ledge about 100 meters wide.

Even as we were trying to locate the route over the

confusing boulder field, Sanjit’s

voice crackled over the radio:

“Ashu come in come in. The ITBP guys have arrived on their

SRP”.

We were happy to see the post commander of Nelang with a small detachment of Jawans, INSAS Rifles slung across their shoulders. We chatted up waiting

for the team to regroup as the ITBP team caught up with us. They had started

that morning from Nelang and were

there near our campsite by 0900 Hrs.

Chatting up with the

post-commander I gathered, he has been posted at Nelang for the last three

years and belonged to Dehradun originally.

“बच्चों का पढाई?” I asked

“बड़ा वाला IIT कर रहा है कानपूर से” he said. The father

in me could almost feel the swelling of his chest in pride.

The soldier at the northern frontier had been able to see

his eldest son through the one of the best technical education the country can

provide; Perhaps the best in this part of the world! I was happy for him.

A little ahead beyond a fast flowing stream was a large rock

with the usual red pennant on a tall flagpole indicating Lal Devta #3. Up ahead the vast Changdum

plains opened up; gigantic fans of glaciers dead many years ago upon which a

luxurious pasture had developed, dotted at this time of the year with pretty

yellow flowers.

Soon we saw a shepherd from a distance whistling merrily.

Coming closer I could see the unique facial description of Govind Singh as I had heard earlier- remnants of his years of

struggle for livelihood through the dangerous terrains of high mountains. Here

was a man who had a hand-to-hand combat with a Himalayan Bear.

He went about his assumed role of the “host” merrily. Soon

tea was served as the ITBP team got busy in pitching their tents and we got

busy in clicking our cameras trying to pose with the gun-toting soldiers.

They were going to camp along with their old friend Govind that night. They intended to come with us till their last patrolling point and after a night's rest at this camp, would go back to their post next day.

They were going to camp along with their old friend Govind that night. They intended to come with us till their last patrolling point and after a night's rest at this camp, would go back to their post next day.

Just about two kilometers ahead of Changdum, where the course of the Chorgad takes a wide sweeping turn towards far left , we went past

the Misora Camping ground sprinkled

with floral dots of yellow and purple. The flowers were getting ready to bloom

and perhaps by the end of June the place had the potential to become a mini Valley-of-Flowers.

A massive scree slope was now looming ever closer at whose

feet the Chor Gad flowed swiftly. The

trail led diagonally over this exposed slope and high above a sizeable herd of Bharals grazed about merrily threatening

our passage with potential rock fall.

The passage went smoothly as we entered level ground now,

heading north again after the westerly diversion on the slope.

The trail now ran by the riverside causing another pretty

marine-drive. We were in the Demoche pastures

where the Demoche Gad confluences with the Chor Gad on its true right. The river is

not difficult to cross here and on the far side we could see groves of Birch, many potential camping spots and

an abundance of pastures for grazing.

Lost in that ethereal beauty of the pretty valley, resting

by the riverside we regrouped and had our lunch unaware about the terrain that

was about to hit our trail.

After the Demoche Gad

marine drive, at the end of the pleasant walk along the left bank of Chor Gad, the trail suddenly winds

nastily upwards to the crest of a spur coming out of the Nakurche complex, a spur that pushes the bed of the Chor Gad sharply due west.

After a sudden rise of about 50 meters the trail levels out

and enters the wide fan of the moraine of the Nakurche Glacier coming in from the right, from the east. The

snowline of this glacier has receded much farther up; what remained on our

trail was a massive boulder field.

Immediately afterwards one comes across a shepherd shelter

perched on top of a precipice directly looking down at the Chor Gad coursing through about 300 ft below. Just ahead was the

bad patch everyone had referred to earlier.

“मैदान के बाद थोड़ा ख़राब रास्ता है. फिसलन वाली मिटटी है थोड़ा. वैसे हम जा रहे हैं, घोड़ों के लिए रास्ता बना लेंगे.” Tilak Raj had informed us during our

little chat up at Misosa.

“Last का 200 meter लगभग थोड़ा ख़राब है. बस उसके बाद Thandapani आ जाता है snow bridge के बाद. ऐसी कोई बात नहीं है , थोड़ा step

cut कर के और जूता मार के आराम से जाया जा सकता है”- the briefing by our

friends in ITBP had been more reassuring.

This was decidedly a bad patch of about a furlong and

“kharab” had been a serious understatement. There were myriad rain water

gullies running through a broken bank of loose scree. The Chor Gad, releasing itself from the icy confines of its upper

valleys, was foaming about 250 ft below. Steps had to be cut for the laden

porters and we had a cautious passage except for the minor mishap of Nitin. He lost a footing and was found hanging

on to dear life on all his fours upon that slippery slope. His ordeal was over

a few minutes later when one of our Nepali

porters jumped across to lend a reassuring hand.

Soon after the patch of bad scree the trail levels out with

the river and a passage has to be found to the right bank over a crevassed snow

bridge. Since all local navigational instructions had depended on this snow

bridge for crossing over the Chor Gad,

I assumed the bridge to be of a permanent nature. It certainly appeared so,

looking at the amount of deposition of snow and glacial debris.

The trail slowly rose up the right bank and with in about

half an hour we were resting on a little flattish delta on the southern edge of

the confluence of a stream coming in from our left. A small stone hut with

ramshackle roofing dominated the scene. Some firewood was littered around. We

had reached Thandapani camp.

|

| (Thandapani CG, Upper Chorgad view in background) |

I walked up to the edge of the tabletop and had a look at

the confluence. The Thandapani stream

was bringing in a respectable volume of muddy brown water to merge with the

relatively clear body of the Chor Gad.

Over the furious flow of the Thandapani was

a small natural rock bridge, which had been further reinforced by rock masonry,

most probably by the local shepherds, as Tilak

had mentioned.

“The chap was right. Tomorrows trail looks to be on this

right bank only!”- We were discussing, even as our anxious eyes started tracing

out the trail rising rapidly up towards the crest of a spur that defines the

southern boundary of the Dudhpani valley

up ahead. Soon Vinod managed to

engineer a little water hole on the sandy shore of the Thandapani stream, which provided bucketsful of clean water for the

entire camp.

The shepherd shelter served as a warm kitchen for the

evening and the bright moon heralded a feast of night photography in the coming

days; we were soon to enter the kingdom of snow.

Terrain conditions were exactly as per the imagery in the

EOSDIS website. We had yet not been obstructed by snow and did not expect to be, at least till the next campsite. Weather was still holding good as per

predictions and we were at the gateway of the upper Chor Gad valley covering 24 kilometers in 2 days with altitude gain

of about a thousand meters.

“Not bad!” I mused “if we continue this way we should target

to be over the pass in next 4 days!” – I wished dearly that the weather and

team health held good. Porters looked to be in good spirits without a grumble

about the two consecutive long marches carrying double-loads.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>

The trail next day dipped down to the bridge over the Thandapani and then sharply rose up

about a hundred feet to land us on another tabletop of rock and scree. The

trail hence wound steadily up for about 200 meters till the crest of the spur

that bisects the right bank of Chor Gad

between Thandapani and Dudhpani valleys, almost plonk in the

middle. We had already crossed the 14000 ft mark and the exertion was telling.

On the far bank we saw the moraine filled slopes dropping in

sheer precipices from a ridge-line about a 1000 meters above us.

Soon the trail levelled and dropped down to the lovely valley

of Dudhpani. True to its name the

water was clear as spring water although it clearly was coming from glacial

melts and was passing from under snow beds and ice sheets. But what a contrast

with Thandapani!!

Our intended campsite was in the next valley by the banks of

the Bushaheri Nala at Kalapani! I wondered for a moment if the name

had anything to do with the color of the water source nearby. Didn’t appear to

be too palatable or potable an idea!

We didn’t have time to partake of the beauty of the lovely Dudhpani valley to the fullest. It is a

recommended halt for future travellers into the valley. One just has to push an

additional hour after reaching Thandapani

the previous evening!

|

| (Sharp ascent ahead of Dudhpani) |

“रास्ता ठीक नहीं है यहाँ से Sir. निचे जाना पड़ेगा नदी से. वैसे camp site दिख रहा है यहाँ से”- called out Vinod, the lead scout, on the radio.

Apparently our current trail headed into a massive landslide

zone to skirt which we would have to climb another 1000 ft higher.

(We realized our mistake later. We should have started our

diagonal climb much higher up in the valley of Dudhpani. That would have

allowed us to gain the crest much above the landslide area.)

The sharp descent to the bed of Chor Gad, the subsequent river crossings over the network of snow

bridges and final climb to the terminal flats of the Kalapani Glacier added at least an hour of delay to the days work.

The snow conditions helped in all the crossings; otherwise it would have been a

nightmare to traverse that patch along the river. Future parties shall be well

advised to take the upper bridle path from Dudhpani

to Kalapani.

Kalapani (As in SoI Map) or Nakurche (US Army

Map-1952) was the most picturesque camping ground we had settled into since

the beginning of the expedition.

A network of streams fed a small glacial lake near the brim

of the basin by the riverside. The dark color of the rocks on the stream-bed was

indeed rendering a blackish hue to the otherwise clean and transparent

water. It looked as if a clear stream of water was flowing through an

undisturbed coalfield camouflaged under various hues of green, brown, yellow,

purple and white.

|

| (The Kalapani stream near campsite) |

Rajender and I reconnoitred ahead for about a kilometer to verify the ground conditions. From now on we

shall be on uncharted terrains solely dependent on features, landmarks and the

GPS.

Snow conditions did not spring any surprises.

The entire valley of Kalapani

was under a white sheet just about half a kilometer ahead of the camp. Some

hints of brown were visible on the northern walls of the bounding ridges but

not enough to serve our purpose. The long lateral ridges, which were supposed

to lead us to the head of the glacier, were totally snowbound. Brown patches

there would have surely helped our speed and safety. But all in all we were

happy with our assessment.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Continued in Part III

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Continued in Part III

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

[i] pp 139- “Loss

of Memory and Continuity of Praxis in Rampur-Bushaher, Contemporary Visions in

Tibetan Studies, Dr Georgios Halkias, Serindia Publications-2009”

[ii] pp94- Route#

153- “Results of a scientific mission to India and High Asia- Vol III”-

“Hermann, Adolphe and Robert De Schlagintweit”,1860.

Lama&Nunnilangpass.jpg)

Hundes_seen_from_Tsan_Tsok_La1882.jpg)

GangotriValleybetweenBhairoughattiandGangotri,Griesbsach,1883.jpg)

waterfall.jpg)

GroupHunias&Niticoolies,ShirkiaCamp,Hundes,North_of_NitiPass,Griedbach,1882.jpg)

.jpg)