The Tale of the Jadhs of Jadhung

“They must have cooked the name up“ I thought when one of

the officers of the Jadung post said…

|

| (The Janak Taal - nestled pretty in the Jadung Gaad valley- June 2013) |

When the names that one had been hearing all along the

valley with such apparent Tibetan influence, (Jangla, Kopang, Karcha,

Nelong, Sumla, Dumku, Pulamsumda etc to name a few) how come such a starkly

hindu name “Janak”? the Sage-King and famed father of Seeta of “Ramayana”! I was looking at the officer in silent

bewilderment.

We had just reached the Jadung

post in Central Nelang watershed,

after a 50 Kilometer drive from Bhaironghati

along the fair-weather road off the national highway to Gangotri. In fact we were thankful to

have left the Gangotri highway,

crammed up with intense pilgrim traffic….

|

| (The Jadung Village/ Post seen from about a kilometer) |

I remembered this

document because this was the only document we had found before the expedition

that had any description of the terrain ahead of the Jadung village.

|

| (A Jadh Lady from the Bagori village near Harsil) |

The ITBP surely had not cooked

up the name of that pretty jewel of a lake!

Quoting Shanti Devi as interviewed around January 1997…

Upon being asked “

Who are Jaadhs?”

“There is a bridge near Lanka in Bhairon valley. This is

across river Jaad Ganga. The story goes that close to the place of its origin

King Janak did his penance. There is a lake close by and its water flows

into this river. So the river is named Jaad Ganga. Our people lived near

the lake close to a khala (small

stream) that is our village. We get drinking water from there. That is why we

have been named Jaad. Similarly all those living on the banks of the river

Ganga are called Gangadi. In the Garhwal area all those living close to the

Jaad Ganga are called Jaad as well as the people of Mukhaba and Dharali

village, called Buderu in the local language. Our caste is not Jaad but Jat

Merut. We are called Jaad by virtue of our being from the banks of the river

Jaad Ganga. We are originally the dwellers of Jadung village. There were two

villages - Neelang and Jadung.”

|

| (Interview with Shanti Devi- Jadh Weaver from Dunda) |

“Earlier we used to

move up and down for six months from Jadung, and went up to Chorpani. We first

came to Bagori, then to Dunda and then to Chorpani. While we were away for six

months the Army jawans (soldiers)

took control of our land. After taking over Jadung they allowed us to come back

and till our land for one year. There is no dearth of water there and it does

not snow there in summers. Since then, however, we have not been allowed to go

there. It snows there from Paush (December/January) onwards.”

The Jadhs of Jadhung (Jadh-Dung)

|

| (The ruins and remnants of the Jadung village- June 2013) |

|

| (Jadh ladies in traditional dress) |

The name Jadung

seems to have come from the compound word Jadh

(name of the tribe that inhabited the valley)- Dung (Mountain).

The British map-makers have mentioned it as "Jadhang" in the "Survey of India" maps. But all local residents of Uttarkashi mention this village as Jadung (perhaps Jadh-Dung). The pronunciation agrees well with the nomenclature explained at the beginning of the paragraph.

The British map-makers have mentioned it as "Jadhang" in the "Survey of India" maps. But all local residents of Uttarkashi mention this village as Jadung (perhaps Jadh-Dung). The pronunciation agrees well with the nomenclature explained at the beginning of the paragraph.

The Jadhs are a

tribe of people who identify themselves with the Jadh Ganga valley. In the

ancient days, agriculture, livestock and commerce drove the economy of the villages

of Jadh-Dung and Nelang that they used to stay in.

The Jadh population is estimated

at around 2500 today of which more than 60% are residents of the Kinnaur valley in Himachal and the rest in the villages of Harsil and Dunda in Uttarakhand.

One could see about 50 odd acres of tillable land that was

surrounding both these villages respectively when we visited there in 2013. That

can be considered reasonable for a village of about 30 odd families,

especially with additional income from livestock and commerce.

It appears, in spite of their Bhotiya origins, the Jadh

people have elements of Garhwali culture

and ethnicity. They have the Garhwali

Rajput surnames like Negi, Rana and Panwar.

|

| (A Jadh festival being celebrated) |

If one wishes to delve deep into the history of the Jadh Ganga valley, the freely

downloadable documentation of Sino-Indian

border discussions are a good starting point.

A good deal of insight into the region is also obtained from

the book “The Raja of Harsil”,

written by Robert Hutchison. The book provides a biographical sketch of Fredrick “Pahari” Wilson of Harsil and captures almost every European visit to the Bhagirathi valley in the period of 1840-80.

Apart form that, early European

travellers to the Upper Taknore Patti

during the early explorations to the source of Ganges mention about the Nelang-Jadhang

villages.

(The entire Bhagirathi

Watershed upstream of Harsil including the headwaters of Jahnavi was called Upper Taknore Patti or

Malla Taknore Patti as per official records of the Garhwal state)

John Hodgson, J B

Fraser, James Herbert, Prince Waldamer of Prussia, Dr Hoffmeister, Col Fredrick

Markham, C L Griesbach and S J Stone are some of those notable few who

visited the area in the 150 years between the first European visit and the independence of India.

The Nelang

watershed remained mysterious and obscure for a long time because of the

difficulty in accessing it from the Bhagirathi

valley, the tall walls of the Nelang

Gorge at Bhaironghati barring the

way.

The easiest access was from Tibet over the Tsang Chok La

or Jelu Khaga as the Taknoris called it. This may account for the influence of the Budhhist religion and customs that may

have proliferated from Tibet in the

late 1600s and early 1700s during the time of the 6th Dalai Lama.

Fraser in 1815,

mentions in his notes that, Tibetans

used to carry out raids in the Nelang and

Harsil area and on one occasion

destroyed a whole settlement near Mukhba

village in Harsil valley. Apparently,

people from Bushaher and Supin valley also used to carry out

similar raids in the Tibetan areas East of Nelang watershed, sometimes all

the way till Mana pass.

Lama&Nunnilangpass.jpg) |

| (A Jadh villager with a Tibetan Lama- below Jelu Khaga on the Jahnavi side, CL Greisbach-1883) |

Apart from the above, as Gerard

mentions in his book “An account of Koonawar” in 1820, armed cavalry from Bushaher state have been said to cross

into the Nelang area over a pass

called Chunsa-Khago to collect taxes

and dues. State Archives of the 1700s indicate rift between the Bushaher and Garhwal regarding matters relating to collection of taxes and

tributes from the Nelang tract.

*******************************************************

A Note about the name Chunsa

Khaga:

|

| (The isometric 3D view of the probable location of "Chunsa Khaga" as described by Wilson and Gerard) |

The Bushaheris and the Taknoris used the term “Khaga”

for pass, more specifically “a pass over snowy ranges” exactly like they used

the term “Danda” for passes over

lesser heights. . The other names of the high passes that connected Bushaher with Upper Taknore Patti of Garhwal are Lam-Khaga, Chhot Khaga etc.

Evidently the name Chunsa-Khaga

indicates – The High Pass to Chunsa or

Nelang. In fact Wilson mentions the name “Changso

Khaga” to be one of the most difficult passes between “Upper Taknore” and “Kinnaur”. The description he provides of this pass

matches exactly with that of Capt A

Gerard.

Thus it may be suspected with reasonable conviction that Capt. Gerard or his publisher may have

made a typographical error by writing the name as “Chunsa-khago”.

**************************************************************

**************************************************************

|

| (The end of the Anglo-Gurkha war in 1815. Signing of the treaty of Sagauli) |

Things took a dramatic turn in the second decade of 1800s

after the British got involved in the Garhwal

affairs following the Anglo-Nepalese war

of 1813-15. This is also the same year that the Russo-Persian treaty was signed and the “Great Game” started between the British

and the Russian Empire, which was

to last for almost the next 100 years.

|

| (Raja Sudarshan Shah of Tehri. The Garhwal state was divided into 2 parts after the Gurkha war in 1815. Sudarshan Shah became the king of the newly formed Tehri Garhwal state) |

Around the same time, J

B Fraser visited the Upper Taknore valley

around 1815 in his search for the source of The

Ganges and documented his experience with records and paintings. Though he

had to come back from Gangotri, his

documentations threw a new light on the topography of the area around the

source of Ganges.

He wrote about the existence of Chaunsah or Nelang and about the Jadh Bhotias. His was

the first record about the summer migration of the Jadhs to Harsil area.

|

| (James Bailey Fraser- The painter who visited Gangotri and mentioned about Nelang and its inhabitants in 1815 even ahead of the surveyors of SoI) |

Lt Herbert returned

to the Upper Taknore valley again in

the August-September period of 1819. Accompanied

with the “Panda” of Mukhba village, he became the first European to traverse up the Jahnavi River and reached Nelang on the 13th September

1819.

He mentions that the Jadh

people of Nelang and Jadung were apprehensive of European

incursion and discouraged him from exploring till the pass to Tibet. Based on his interactions he

established that The Jahnavi originates

much closer to Nelang and on the

south side of the pass to Tibet; not

from far off Chaprung, as was

previously thought.

|

| (John Hodgson-first European to see Gomukh in 1817 He went on to be the Surveyor General of India His colleague Lt James D Herbert became the first European to visit Nelang/Jadung in 13th Sept 1819) |

He brought commercial logging to Upper Taknore Valley and supplied wooden logs and slippers to two ambitious projects of the British- The Ganga Canal project and the Indian Railways. It is said that “Hulseyn/Hodgesingh” Sahib (the local name for Mr Wilson) amassed a fortune of many crores of rupees in just over 2 decades by circa 1860!

The British suspected

that the pass of Tsang–Chok-La (Jelu

Khaga/ Jeela Kanta) in Nelang valley

could be an easy gateway for attack by the Russians.

They wanted pass well monitored and the accesses to and from the pass to be a

well-guarded secret. They used Wilson as the eyes and the ears of the British Government spying on any foreign

traveller who wished to travel up the Upper

Taknore valley.

Hundes_seen_from_Tsan_Tsok_La1882.jpg) |

| (The crest of the Tsang-Chok-La or the Jelu Khaga. It is one of the easiest access routes to Tibet from the Indian subcontinent) |

(Hutchison mentions Gundar Pass in his biographical sketch

of Wilson- perhaps a Garhwali name for the pass that Gerard mentions as Chunsa-Khaga. The start-end points and other geographical description

of the pass are exactly the same).

|

| (The Chunsa Khaga- Detailed map. Access from Baspa to Nelang) |

|

| (Prince Waldemar of Prussia- His intended excursion into the Nelang watershed was thwarted by F Wilson successfully in 1847) |

He (Wilson) was later appointed as the agent of the King of Tehri State in the Upper Taknore Valley including the Nelang tract and was also given the responsibility of rehabilitating the area in 1849.

Wilson on his part

helped establish the communication link between Harsil and Nelang by way

of his several architectural ventures and also got few Bhotiyas from the Baspa Valley

to settle at Nelang. He was credited with the construction of

several bridges over the Jadh Ganga gorge,

perhaps for the first time ever, using both suspension and cantilever

technologies.

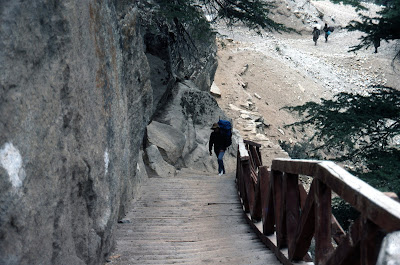

There is reason to believe that the “Plank Trail” that one can see near Hawa Bend en-route Nelang on

the true right of the Jadh Ganga may

actually have been a product of Wilson’s

ventures. The trail would have required huge amount of wood and ingenuous engineering.

Wilson readily fits that description. During and before that period, there is no other example of

such engineering venture in that area apart from those by Wilson who also held the logging license for ”Taknore Patti” and hence had almost unlimited access to high quality Deodar wood.

Remains of The Jadh Ganga Toll Bridge, his first venture in 1844, stand tall even today just by the side of the modern day steel Girder Bridge over the Bhaironghati Gorge. The aforesaid Plank Trail leading to Nelang is merely 3 Kms from this place.

|

| (Wilson's Jhoola over the Jahnavi river in 1850s) |

Remains of The Jadh Ganga Toll Bridge, his first venture in 1844, stand tall even today just by the side of the modern day steel Girder Bridge over the Bhaironghati Gorge. The aforesaid Plank Trail leading to Nelang is merely 3 Kms from this place.

|

| (The ingenuous plank bridge along the right bank of Jahnavi, the ancient route to Nelang, perhaps strengthened by Wilson) |

By this time of mid 1800s, the name “Chaunsah” went out of popular use. The Garhwali names- “Nelang” and

“Jadung” became more popular.

GangotriValleybetweenBhairoughattiandGangotri,Griesbsach,1883.jpg) |

| (The route between Bhairon Ghati and Gangotri as seen in 1883 by C L Greisbach) |

Griesbach mentions

in his journals that, the Jadhs of Jadung and the Tibetan government were not in good terms, at the time that he

visited there. The Jadhs had murdered

an overbearing Tibetan beggar-monk and

relations with the district headquarter

at Chaprung were strained.

waterfall.jpg) |

| (The area between Jangla and Gartang Camp Ground on the Jahnavi as seen in 1883 by CL Griesbach during his tour to Nelang watershed ) |

He made an interesting crossing from the Naga over a 19000 ft pass into

the Nilapani Gaad valley and having crossed

the Muling Pass, ended up surveying

the Hop Gad valley that borders the eastern

flank of the Nelang tract. He documented for the first time that Muling La in the Nilapani Gaad (a tributary of Mana

Gaad) valley has been out of use from circa

1850.

Marco Pallis in

his famous exploration up the Gangotri

valley in 1933 mentions about his intent of hiring Jadh Bhotias for porters during his brief halt at Harsil. He believed that like other Bhotia tribes, the Jadh Bhotias would also be strong and hardy and would make for good

high altitude help. He mentions that later on he was disappointed to see the

unsuitability of the Jadhs for his

purpose.

In the 1936-40 period the entire Nelang watershed was mapped with modern methods in which people

such as Lt JFS Ottley and JB Auden played crucial roles.

After the disturbances by the Chinese in 1956 and the

subsequent clearing up of the valley, very few civilians have visited the area.

Two notable Indian explorers Romesh Bhattacharjee and Harish Kapadia visited circa 1990 and documented the Tirpani Gaad /Barreguda Gaad area and Mana Glacier respectively.

Two notable Indian explorers Romesh Bhattacharjee and Harish Kapadia visited circa 1990 and documented the Tirpani Gaad /Barreguda Gaad area and Mana Glacier respectively.

In 2012, a Himalayan

Club team led by Ashutosh Mishra team

went up the Mana Gaad valley and

opened the Basisi Col route to cross

over into the Alaknanda valley

(HJ-Vol 68); a challenging but easier alternative to Kalindi Khal for going to Badrinath

from the Bhagirathi valley.

|

| (Route of the Himalayan Club expedition by A Mishra and team in 2012. The route leads from Mana Gaad valley to Alaknanda valley over the Basisi W Col) |

However, during

all these developments, geographical details of the Jadung valley remained obscure.

Most of the mapping and

documentation focus of the British was

on the passes going out to Tibet namely

Tsang Chok La/ Jelu Khaga, Thag La and Muling La.

Jadung was tucked away too far into the

center of the Nelang watershed. For

example the British Army map of Garhwal in 1936 does not mention about any

detail ahead of Jadung except for

some vague and inaccurate contour lines (including erroneous plot of the origin

of Jadung Gaad)

|

| (Romesh Bhattacharjee and team on the Plank Trail circa 1990) |

Today, nestled in that pretty valley of Jahnavi, the quaint little village of Jadung stands neglected, ruined and forgotten. The intricate

woodworks of old Deodar-pine houses

mutely bear testimony to years of persecution, hardship and eventual prosperity.

|

| (The Jadung village as seen today- June 2013) |

*************************************

Having been aware about the historically romantic story of

the village of Jadung, it did not

take much to decide upon the expedition itinerary of 2013.

Add to that the fact that there is almost no documentation

available about the geographical features ahead of the village of the Jadung, which presented a powerful

objective; a unique opportunity to explore a valley and a peak that was truly

virgin and document it in detail for the first time ever!

We were about to do something that was historical and

pioneering. The lovely vista and centuries old story of human perseverance that

we might witness on the way would be an added bonus.

This was going to be extreme exploration and we had to be

mindful of few things.

1.

We needed a proven team

2.

We had to have robust research backup for

navigating through the terrain

3.

We had to have as much support of weather and

weather forecasting as we could manage

|

| (The Team- Jadung Valley expedition June 2013 L to R top to bottom- Ashu, Kuntal, Bharat, Ravin, Kalyani, Arun, Atam, Sanjit, Anant) |

The Four Valleys of the Jahnavi(Nelang) Watershed:

The Nelang watershed

drains water from four major valleys. Three of these vales have a generally

North-South orientation and only one, The Mana

Gaad valley, had a East-West orientation. The three passes that have the

International border and water parting line to the North and the Jadh Ganga to the south are Chor Gaad Valley in extreme west, Tirpani Gaad Valley in the extreme east

and the Jadung Gaad Valley that lies

plonk, in the middle.

The Tirpaani Gaad valley

has seen trade traffic since centuries and was the traditional trade route from

the Hop Gaad valley area in Tibet over the famous passes of Thag-La and Tsang-Chok-La. I have attempted a brief description of the valley

in the narration of our adventure of the Auden’s

Trail. The history of this valley is well documented by Atkinson, Oakley, Heinrich Harrer, Romesh

Bhattacharjee and Harish Kapadia.

.jpg) |

| (Nelang Watershed- Chor Gaad, Jadung Gaad, Tirpani Gaad in North-South orientation in center frame The West-East layout of the Mana Gaad at the bottom right frame) |

Chor Gaad or “The Thieves’ River” had another interesting story. It was so named because the harassed traders used to use this almost-hidden valley to evade the taxes imposed by the Kingdoms of Garhwal and Rampur Bushaher. Romesh Bhattacharjee, Harish Kapadia and Tapan Pandit have already written about this interesting valley.

It is the Jadung Gaad valley

in the middle that bears little geographical description in the historical

records. Atkinson’s Gazetteer describes

the village and carries data about its economic performance in the late 1800s.

Similarly, the documents referred to by the Government of India for boundary

discussions are essentially extracts from the archives of the Kingdoms of Garhwal and Rampur Bushaher, most of the data is about the rights of taxation

exercised by various administrations. None of those documents bear any detail

of what lies between Jadung and the

bounding ridges of the water parting lines.

In the age of Google

Earth, NASA Worldwind and Bing Map it is possible to have a look

at the geographical features through satellite imagery and have a broad idea

about the terrain by superimposing the Digital

Elevation Model of the globe, available almost freely on the Internet. We utilized this modern-day

technical advantage to the hilt while planning the route.

Route Plan:

Our initial research revealed a beautiful blue lake roughly

200X100 Meters in size, about 10 Kms ahead of Jadung village. One can clearly see a well laid out track leading

all the way to the lake and then on along the Jadung Gaad for few Kms ahead. Perhaps the Jadhs of Jadung used it

in old days and the troops guarding the border use it in the current days, we

surmised.

|

| (Janak Taal area- 10 Kms due North of Jadung Village) |

It looked difficult to follow

the main valley to reach the headwaters.

However, hope beaconed to the true right of the valley near

the lake where a dead glacier appeared leading up to a high plateau ruled by a

beautiful looking peak. The peak had shoulders on to its North and South both

of which seemed to have doable cols that could lead one to the neighboring valley

to the west, The Chor Gaad valley. Of

the two cols the South Col was 200

meters less tall but had a much steeper angle of descent. We decided to throw

our lot with the South col.

|

| (The terminal Cwm of the Janak Glacier showing The Nakurche Peak, Nakurche North/ South Col) |

Even the traverse over the Chunsa Khaga was a rare trek. Only one team has been recorded to

have crossed this in the last 200 years..

Tapan Pandit from WB carried

out the traverse in modern times, as late as the June of 2009, over this

interesting and elusive pass.

We wished to execute the plan in the first half of June. Upon

tracking the forecast for almost over a week during late May, I observed one

strange pattern! There was consistent forecast of the weather going bad after

the 15th of June with significantly high precipitation predicted in Himachal areas compared to the Bhagirathi valley. That was a bit

strange. Usually the June rains are due to the South West Monsoon and the monsoon depletes into lesser

precipitation as it moves west from Uttarakhand

to Himachal. Only later would I

connect the dots after the massive cloudburst in the Kedarnath valley 2 weeks later.

|

| (The Jahnavi Exploration Expedition Route Plan covering Jadung and Chorgad - June 2013) |

Continued in Part 02

Detailed captioned album here

Trailer of Team DVD

*************************************************

References:

Books

and Journals:

1. JB Fraser: “Journal of a tour through

part of the snowy range of the Himala Mountains and to the source of the Rivers

Jumna and Ganges”-1820

2. Alexander Gerard: “An account of Koonawar”-

1820

3. Dr W Hoffmeister: “Travels in Ceylone and

Continental India”- 1847

4. Col F Markham: “Shooting in the Himalayas”-

1854

5. Wilson “Mountaineer”: A Summer Ramble in the

Himalayas- 1860

6. E

Atkinson: Atkinson’s Gazetteer-1882

7. CL

Griesbach: “Geology of the Central Himalaya”: Memoirs of the Geological Survey of India- Vol 23- 1891

8. S J Stone : “In and beyond the

Himalayas”-1896

9. The Himalayan Journal Vol 6- 1934

10. The Himalayan Journal Vol 12- 1940

11. The Himalayan Journal Vol 66- 2010

12. Col R Phillimore: “The Mountain Provinces- Garhwal and Sirmor”: Historical Records of the Survey

of India, Vol 3-1954

13. Robert Hutchison: “The Raja of Harsil- The

Legend of Fredrick ‘Pahari’ Wilson” 2010

Articles and Papers:

14. “Report of the Officials of Government of

India and the People’s Republic of China on the boundary Question- Part 3- 1960

15. “The

Descent of Pandavas-Rituals and Cosmology of the Jads of Garhwal”: Subhadra Mitra Channa: European Bulletin of

Himalayan Research 28: 67-87 (2005)

Websites:

16. “Tehri Garhwal- Brief History”: http://www.royalark.net/India/tehri.htm

17. “Interview

with Shanti Devi”: Mountain Voices –

India- Garhwal and Kinnaur http://mountainvoices.org/Testimony.asp%3Fid=38.html

18. “Interview

with Champal Singh”: Mountain Voices –

India- Garhwal and Kinnaur http://mountainvoices.org/Testimony.asp%3Fid=37.html

19. “Interview

with Yagjung”: Mountain Voices – India- Garhwal

and Kinnaur http://mountainvoices.org/Testimony.asp%3Fid=33.html

20. The Jads

of India: Joshuaproject- http://www.joshuaproject.net/people-profile.php?peo3=16973&rog3=IN

GroupHunias&Niticoolies,ShirkiaCamp,Hundes,North_of_NitiPass,Griedbach,1882.jpg)

16 comments:

thank u very much for great information of my land and my origin.I never been my for fathers village.I am a Jadh.I am surprised to see this page.Most of information about my valley is authentic n my family had great history in jadh tribe.i use to hear from my grand parents how they use to visit Kailash mansarovar from my valley.I uncle still use to visit my village Nelang..this jotendra singh negi.

I am from this valley.My village is Chongsa.I never went thr my grand father use to tell me abt Nelang and Jadung.I am surprised to see history abt my land. Thank u very much bringing and informing abt history of my land.But few things r not very true anyway i like it..thanks

jotendra singh

Thank you Jotendra for your comment. I am indeed overwhelmed with emotion that I could be of help to make you dig deeper into the ancient times of your people. Thanks for leaving that comment. I did some further work on the historical aspects which you may find useful which is published in our recent article on Chunsa Khaga of the Tsor Gad valley of "Chongsa" as you say it :-)

Are permissions required to visit Nelang and Jadhang. Though not a trekker or an explorer, these two villages and the Jadh Botiyas have been in my mind since last 2 years. And I do not know how this idea came to me.

i would like to read it..a s a Jadh tribe i would love to know everything belong to my forefathers .It is surprised to see such wonderful land .my granny used to tell me everything abt sang and chungsa..our people still use to worship our deity and our shepherd use to go in summers .My father had many sheeps n horse ..now we all left becoz no trade n no education n hospital..our younger generation now studying in doon aur delhi.it is very good to see n read information abt my people..thank very much ..

Thank you Jotendra for your kind compliments. I am overwhelmed with joy that my work has been of some use for you to link back to your ancestral history.

Mario ... I do appreciate your curiosity and can empathise with the feeling. For me it was the first view of that board that says entry is prohibited. Can not say for you..perhaps a similar cause if you have visited Gangotri..or perhaps you may have read the article of our exploration or that of Tapan Pandit's of H Kapadia or R Bhattacharjee's account..or may be JB Auden's or JB Fraser's accounts. To answer your question yes, you need a written permission from the DM Uttarkashi allowing you to visit the Nelang valley (specific locations) for an approved period of time.

Hey Ashutosh,

As I discovered just a few days ago, apparently the Tibetan name for the entire Himalayan Garhwal is also Chongsa.

Ref 'Physical Geography of Western Tibet', page 2 by H. Strachey (1854).

https://books.google.co.in/books?id=FLJKJVmKq-YC&pg=PA1&lpg=PA1&dq=gyagar&source=bl&ots=JIbz4F9rFM&sig=gwXMZ-Ix5hdiwVj-OHBi3etPkz0&hl=en&sa=X&ei=nrP4VJ7-NsuUuASMgoGICQ&ved=0CBwQ6AEwAjgo#v=onepage&q=gyagar&f=false

Cheers, Sudhin

Hi Sudhin...glad you pointed that out.. Guess when he distinguishes Garhwal and Himalayan Garhwal he was precisely talking about the icy ranges north of the lower Garhwal mountains. ..what the Tehri Durbar called as Taknore Range... the Tibetians essentially used to contend that the Upper Taknore range came under the Chongsa province. This however was contested by Tehri Kingdom backed by the British. ..and around Wilson's time the durbar had erected border pillars atop Tsang Chok La pass. .. in the context of the history during Starchy;s !! can have such mentions :-)

I am researching for Nelang and Jadhang villages especially their historical origin - seeking evidence for their claims under Forest Rights Act 2006, under an ICSSR sponsored Research Project on Sustainable Development of Mountain Communities undertaken in the Upper Taknore villages along with other villages in Bhatwari Block of Uttarkashi District. Your blog has provided important references. Thanks a lot. I would be acknowledging your blog.

Thanks for the wonderful work

Warm regards

Malathi

Dr.A. Malathi

Assistant Professor, Department of Social Work, University of Delhi

Hi,

Interesting read. Came yesterday from Jadung. To inform you all, now one can procure permits from Uttarkashi up to Nelang.

This is as a result of continuous efforts of the Hotel Association Uttarkashi to open the Nelang Valley to tourists. So on Sept 28th 2015 a group of 30 of us with special day visit were allowed up to Jadung.

We hope with the support of ITBP and the Forest department other areas in the Nelang valley become accessible.

This route - from the Chitkul end to Nelang and then from Gangotri to Kedarnath and then onto Saharanpur - seems to be the one followed by KIM and Teshoo Lama in their quest (see the last part of the book by Kipling).

I am curious how Kipling could have imagined such a difficult route at all.

Perhaps Ashutosh can identify Shamlegh - the place in Chini valley from where Kim starts back?

Thanks Yogendran ...for that input. I will check.

But not difficult to imagine. It seems Kipling had met Fredrick Wilson....must have been inspired by him which caused him to portray him as the protagonist in "The Man who would be King". They lived in the same time in history.

Coming to Wilson, he seems to have known about this pass and apparently used it privately to get to Kinnaur. In that case, its probable that the two may have discussed it. Hutchison goes as far as to say (in Raja of Harsil) that Wilson followed two russian spies over this pass to Kinnaur and killed them in an accidental brawl.

So one can put 2 and 2 together. But I am doubtful if Wilson told him about the details of the pass. He was apparently very secretive about the route to and people of Nelong Valley. So unlikely that Kipling would give a faithful description. But I will read and come back to you on this.

Thanks and cheers!!

Wilson in his book "A summer ramble in Himalayas" mentions about this pass explicitly and in fact devotes almost a paragraph to it.

@ Yogendran

Chini is the current day town of Rekong Peo...the HQ of Kinnaur district.

Now the closest i can think of "Shamlegh" is "Shanglah" the name that the british used for Sangla ...about 30 Km before Chitkul ...on the banks of the Baspa

Thank you for this detailed blog post. Am planning to visit this November. Hope to be able to go and see this beautiful place weather permitting!

Would you have any idea of the current status of roads and whether civilians are allowed to Janak tal?

Hi...Yes you can visit after organising a permit thru any local tour operator

Post a Comment